Planorbis: Classification, Ecology, Identification, and Importance

Planorbis is a genus of air-breathing freshwater snails in the family Planorbidae, commonly called ram’s horn snails for their flat, disk-like shells that coil in a single plane. Species in this genus are hallmark residents of ponds, ditches, canals, lake margins, and quiet river backwaters, where they graze biofilms and detritus and help recycle nutrients. Planorbis is also notable for physiological adaptations to low-oxygen waters and for its paleontological continuity from the Jurassic to the present, reflecting long-term ecological success.

Classification of Planorbis

| Rank | Taxon | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukaryota | Nucleated cells with membrane-bound organelles |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Multicellular, heterotrophic organisms |

| Phylum | Mollusca | Soft-bodied invertebrates, often with calcareous shells |

| Class | Gastropoda | Muscular foot and radula; undergo torsion during development |

| Order | Hygrophila | Freshwater pulmonate snails with an air‑breathing mantle cavity |

| Family | Planorbidae | Planispiral, sinistral shells; often with hemoglobin-bearing hemolymph |

| Genus | Planorbis | Flat, disk-shaped shells with a peripheral keel; sinistral coiling |

Habit and habitat

Planorbis species inhabit shallow, still, or slow-flowing freshwater bodies with abundant submerged vegetation and periphyton. Typical habitats include weedy pond margins, ditches, oxbow lakes, canals, and the vegetated edges of lakes and slow rivers. They graze on algae, diatoms, and detritus, contributing to nutrient cycling and the control of periphyton buildup. As pulmonates, they surface periodically to breathe air, allowing survival in hypoxic or eutrophic waters.

Geographical distribution

Planorbis has a broad distribution across temperate regions of Europe and beyond, with records extending to parts of North Africa and introduced populations elsewhere. The well-known species Planorbis planorbis is widespread across Europe and has been recorded in many freshwater habitats from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. Fossil records indicate the genus has ancient origins, and extant species continue to occupy a variety of lentic environments.

General characteristics of Planorbis

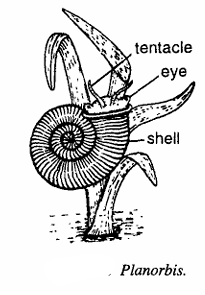

- Animal is enclosed in black, stout and spirally coiled shell.

- Shell is sinistral and discoidal having a depressed or flattened spire.

- Head protrudes through the shell opening. It contains filiform tentacles and a pair of eyes.

- Mantle lobe outside pulmonary cavity is transformed into a functional gill.

- Planorbis also served as intermediate host for larval stages of the flukes.

- Shell: Planispiral (coiled in one plane), disk-like, and sinistral (left-coiling), frequently with a peripheral keel or carina distinguishing species.

- Size: Shell breadth typically ranges from about 9 mm to 20 mm in common species, with shell height much lower due to the flattened coil.

- Body: Soft-bodied with a broad foot; coloration ranges from grayish to brown; hemolymph may contain hemoglobin, giving a reddish tint suitable for low-oxygen environments.

- Respiration: Pulmonate lung; snails surface to take in air and can survive in hypoxic conditions.

- Feeding: Graze on periphyton, microalgae, and decomposing organic matter using a radula.

- Reproduction: Hermaphroditic; lay gelatinous egg masses attached to vegetation or submerged substrates.

Special features of Planorbis

- Hemoglobin presence: Many planorbids possess hemoglobin-like molecules in their blood, enhancing oxygen transport in poorly oxygenated waters.

- Disease ecology: Planorbis and related planorbids are ecologically important as intermediate hosts for trematodes; monitoring their populations aids in understanding and managing parasite transmission.

- Ecological resilience: Tolerant of eutrophic and disturbed habitats, Planorbis often colonizes newly created or altered freshwater bodies.

Identification

- Shell coiling and form: Look for flat, discoidal shells with sinistral coiling; presence of a keel may help distinguish species like P. planorbis from close relatives.

- Size and sculpture: Measure shell breadth and note any carina, growth lines, or surface texture.

- Habitat association: Presence in shallow vegetated waters suggests planorbid identity; behavior such as surfacing to breathe is typical.

- For species-level ID: anatomical (radula and reproductive system) and molecular analyses are often necessary due to morphological plasticity.

Life cycle and reproduction

They are simultaneous hermaphrodites capable of both self-fertilization and cross-fertilization, though cross-fertilization is usually favored to promote genetic diversity. Mating involves mutual exchange of sperm, after which egg masses—gelatinous ribbons or clumps—are attached to submerged vegetation, stones, or detritus. Egg development time varies with temperature and water quality, typically ranging from several days to a few weeks; juveniles hatch as miniature snails and undergo direct development without a free-swimming larval stage.

Anatomy and physiology — more detail

- Shell and soft body: The shell is planispiral and sinistral but often carried upside-down, which can make it appear dextral; shells may possess a peripheral keel and show species-specific sculpture and coloration.

- Respiratory system: Lacking gills, Planorbis uses a vascularized mantle cavity as a lung; surfacing behavior for air intake is common and allows survival in hypoxic conditions.

- Circulatory system: Some planorbids possess an iron-based hemoglobin in their hemolymph, improving oxygen transport efficiency in low-oxygen waters and giving a reddish body tint visible in translucent specimens.

- Feeding apparatus: The buccal mass contains a radula equipped with rows of teeth adapted to scraping microalgae and biofilm; radular tooth morphology can aid in species-level identification.

Behavior

- Locomotion: Slow crawling using a broad foot with glue-like mucus enabling adherence to submerged vegetation and substrates.

- Feeding behavior: Continuous grazing on surfaces, with activity patterns influenced by light, temperature, and predator presence; some species show diel activity shifts, feeding more during dawn/dusk.

- Predator avoidance: Reflexive withdrawal into the shell and reduced activity, together with habitat choice (hiding among dense vegetation), reduce predation; in some planorbids, calcified shell barriers or operculum-like structures protect the aperture from small predators.

Conservation and threats

- Sensitive factors: Acidification, heavy metal contamination, pesticide runoff, and habitat destruction (wetland drainage, river channelization) can reduce local populations or cause extirpation of sensitive species.

- Invasive potential: Some planorbid species can become invasive when translocated through aquatic plant trade or ballast water, potentially impacting native mollusk communities and altering parasite-host dynamics.

- Conservation value: Native Planorbis populations contribute to wetland biodiversity and provide ecosystem services such as grazing on algae; their presence supports predator species and contributes to nutrient cycling.

Human relevance and medical importance

- Disease ecology: While Planorbis is not as notorious as Biomphalaria for transmitting human schistosomiasis, planorbid snails collectively play crucial roles as intermediate hosts for various trematodes infecting wildlife and, in some cases, livestock or humans; monitoring planorbid distributions helps inform public health and veterinary interventions.

- Bioindicator use: Changes in Planorbis abundance and community composition can indicate eutrophication, pollution, or habitat shifts, making them useful in freshwater biomonitoring programs.

- Research value: Planorbids serve as model organisms in ecotoxicology, physiology (respiration and hemoglobin studies), and evolutionary biology due to their varied reproductive strategies and morphological plasticity.

References

- Planorbis — overview and fossil record: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planorbis

- Planorbis — ecology and distribution: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planorbis_planorbis

- Identifying British Planorbis species: https://conchsoc.org/aids_to_id/Planorbis.php

- Planorbis taxonomic record (MolluscaBase): https://www.marinespecies.org/molluscabase/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=182693

- GBIF: Planorbis planorbis occurrence data: https://www.gbif.org/species/165510181

- Planorbidae family overview: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/planorbidae

- Hemoglobin in snails: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1567689/